Quantum-ready workforce tops White House, scientists’ list of needs

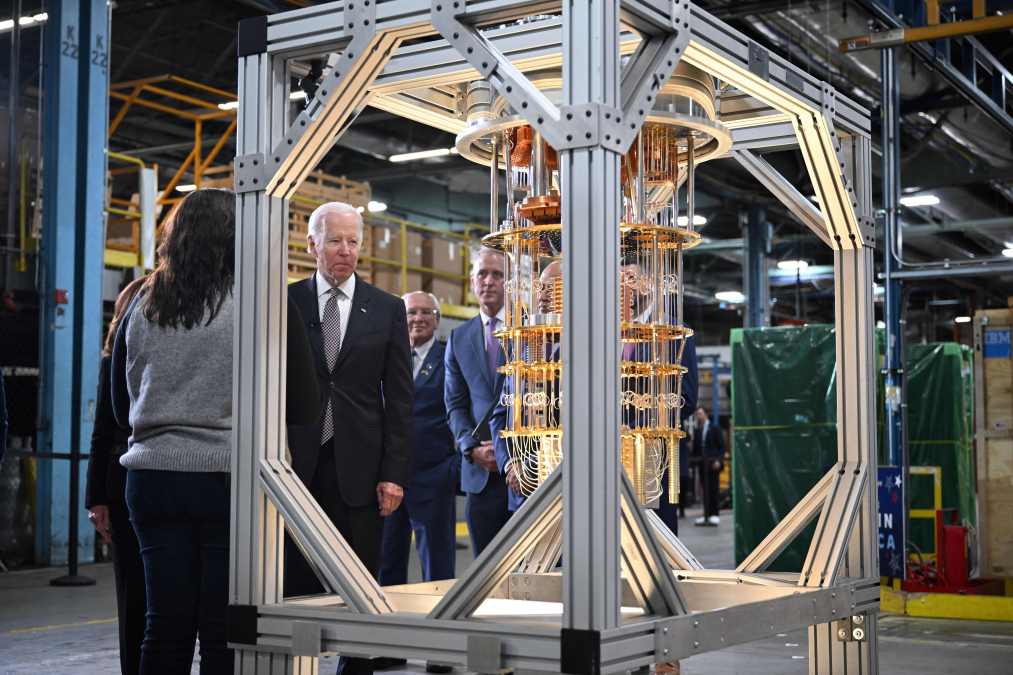

Workforce was the topic on most quantum scientists’ minds when 30 of the country’s best met at the White House on Dec. 2 to discuss the global quantum race.

Leaders of the five National Quantum Information Science Research Centers (NQISRCs) were among the attendees assessing their success accelerating QIS research and development, technology transfer, and workforce development since their launch mid-pandemic.

The National Quantum Initiative Act of 2018 allotted the Department of Energy $625 million for the centers, which have begun integrating companies into the U.S. QIS ecosystem. Gone are the days when monopolies like Bell Labs and IBM funded basic science in house, meaning U.S. investment in accessing the best quantum engineers is more important than ever to winning what has become a global race with China and Europe.

“This is the time to change the model for how you build a technology workforce,” David Awschalom, professor at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering and senior scientist at Argonne National Laboratory, told FedScoop. “This is an opportunity to build a very diverse, very inclusive and very equitable workforce.”

Awschalom participated in the Dec. 2 White House meeting, about half of which he said consisted of roundtable discussions on growing a quantum-ready workforce.

Companies participating in the Chicago Quantum Exchange, housed at the University of Chicago, are more concerned about the talent shortage than they are about even a more reliable qubit, Awschalom said.

Awschalom envisions an ecosystem where “quantum” is no longer an intimidating word for students, QIS is taught in high schools and community colleges, and the development of new technologies launches the careers of students at universities like Chicago State. The predominantly Black university regularly sees impressive students working full-time jobs to stay enrolled or making class sacrifices to care for children, he said.

Alleviating those complications could see tens of thousands more students enter the quantum workforce.

“We realized that to really address these questions properly we should probably have another meeting like this, where we bring in members from those communities to tell us what they need,” Awschalom said.

While no date was set, National Quantum Coordination Office Director Charles Tahan was clear that his door is open, and the White House wants to work together more with the QIS ecosystem, he added.

The second major topic of discussion at the White House meeting were “big” delays in obtaining rare-earth elements and unusual materials found outside the U.S. but required for a lot of quantum components, Awschalom said.

Helium-3 is needed for cryogenic experiments but became harder and more costly to obtain due to Russia’s war on Ukraine, while elements critical to quantum memories can only be mined in a few places globally.

Fortunately the U.S. is adept at nurturing startups, which could prove key to developing compact cryogenics and on-chip memories with silicon-compatible materials, Awschalom said.

The universities of Chicago and Illinois partner on the Duality Quantum Accelerator, which has hosted 11 quantum startups — including four from Europe — for research and development. At the NQISRC level, joint programs are forming between centers.

Since the birth of the qubit, rudimentary quantum processors have begun “remarkably fast” computing and prototype networks sending encrypted information around the world, Awschalom said. The University of Chicago’s 124-mile Quantum Link between it, Chicago and the National Labs serves as a testbed for industry prototypes and will eventually extend into south Illinois.

Whether the first beneficiary of quantum computing is precision GPS for microsurgery, improved telescope strength or some as-yet-unrealized application remains to be seen.

“The one thing we all know for sure in this field is that we don’t yet know the biggest impact,” Awschalom said. “So the United States and our centers have to be prepared; we need to be nimble.”